- Home

- About

- About SCMS

- Directors

- Artists

- Vera Beths

- Steven Dann

- Marc Destrubé

- James Dunham

- Mark Fewer

- Eric Hoeprich

- Christopher Krueger

- Myron Lutzke

- Marilyn McDonald

- Douglas McNabney

- Mitzi Meyerson

- Pedja Muzijevic

- Anca Nicolau

- Jacques Ogg

- Loretta O'Sullivan

- Lambert Orkis

- Paolo Pandolfo

- William Purvis

- Marc Schachman

- Jaap Schröder

- Andrew Schwartz

- William Sharp

- Ian Swensen

- Lucy van Dael

- Ensembles

- Concerts

- The Collection

- Recordings

- Education

- Donate

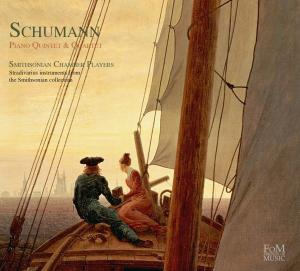

Robert Schumann: Piano Quintet in E-flat Major, Op. 44; Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 47

The Smithsonian Chamber Players (Lambert Orkis, fortepiano; Ian Swensen & Marilyn McDonald, violins (op. 44); Lisa-Beth Lambert, violin (op. 47); Steven Dann, viola; Kenneth Slowik, violoncello) on Stradivarius instruments from the Smithsonian Collection

FoM 36-804

When, in 1842, Schumann turned to chamber music, taking a self-guided tour (with Clara as a constant companion) through the great Classical-era masterpieces for inspiration, he produced, in barely more than nine months, his three Op. 41 string quartets (“dedicated to his friend Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy”), the piano quintet (Op. 44) and quartet (Op. 47) recorded here, and the first of his piano trios, published later as Op. 88 under the title Fantasiestücke. The accomplishment as a whole is nothing short of breathtaking. Writing in the still-useful Cobbett’s Cyclopedic Survey of Chamber Music (1929), Richard Aldrich observed:

Schumann’s chamber music of 1842 is in many ways among the most perfect of all the products of his genius; the purest and most powerful in its beauty, the strongest in its form, best balanced in its substance, and best adapted in its technical means and processes to the expression of the composer’s thought. There is little that seems tentative, experimental, or uncertain in touch. He entered, to all appearances, full-fledged and confident upon the difficult and problematic art of chamber music.

The Piano Quintet and Quartet are frequently performed in large concert halls with a nine-foot-long concert grand piano. Beautiful as such renditions may be, they fundamentally distort the delicate balance of public and private which chamber music of Schumann’s time epitomized. Clara Schumann’s diary entry from Moscow, 1844, is revelatory in this regard: “On Thursday the 2nd of May (April 20 according to the Russian calendar) at 1 o’clock we gave a matinee at our place. We had invited 30-40 people . . . The Quintet constituted the beginning and was exceptionally well liked: I would have liked to play it at my last concert, but the hall is too big for chamber music.” In a typically apposite remark, Susan Youens has written of the Quintet: “‘In this work,’ Schumann seems to say, ‘you can have an orchestra in your parlor.’”

The “concert grand,” as its name might imply, was developed for the large concert hall. Its full cast-iron plate carries a combined string tension approaching thirty tons. Though Clara Schumann, at the end of her life, might have encountered such instruments, those she played at the height of her virtuosity were substantially different, as is the 80-note fortepiano by R. J. Regier played by Lambert Orkis on this disk. The Regier, combining features of pianos of the 1830s from the shops of Ignaz Bösendorfer and Conrad Graf, two of Vienna’s finest builders, is, like its models, constructed almost entirely of wood, lacking completely the composite wood/iron frames of some contemporary non-Viennese instruments. It thus resembles closely the 1839 piano presented to Clara Schumann by Graf, on which both the piano quintet and quartet were written. When combined with appropriately set up stringed instruments, the piano, with its articulate, leather-covered hammers capable of drawing a wide variety of colors, lends Schumann’s writing, so frequently criticized as turgid or muddy, a clarity and luminosity which entirely vindicates his scoring.

—from Kenneth Slowik's liner essay

Listen to the Scherzo from the Piano Quintet in E-flat Major, Op. 44

Price:

$16.00 + $2.98 shipping & handling

On this album:

Robert Schumann: Piano Quintet in E-flat Major, Op. 44 (1842)

[1] Allegro brillante

[2] In modo d'una Marcia. Un poco largamente

[3] Scherzo. Molto vivace

[4] Allegro, ma non troppo

Robert Schumann: Piano Quartet in E-flat Major, Op. 47 (1842)

[5] Sostenuto assai - Allegro ma non troppo

[6] Scherzo. Molto vivace

[7] Andante cantabile

[8] Finale. Vivace